The Z 9’s Eye AF Takes the “Still” Out of Still Photography

(Wait…What? How’s That Again?)

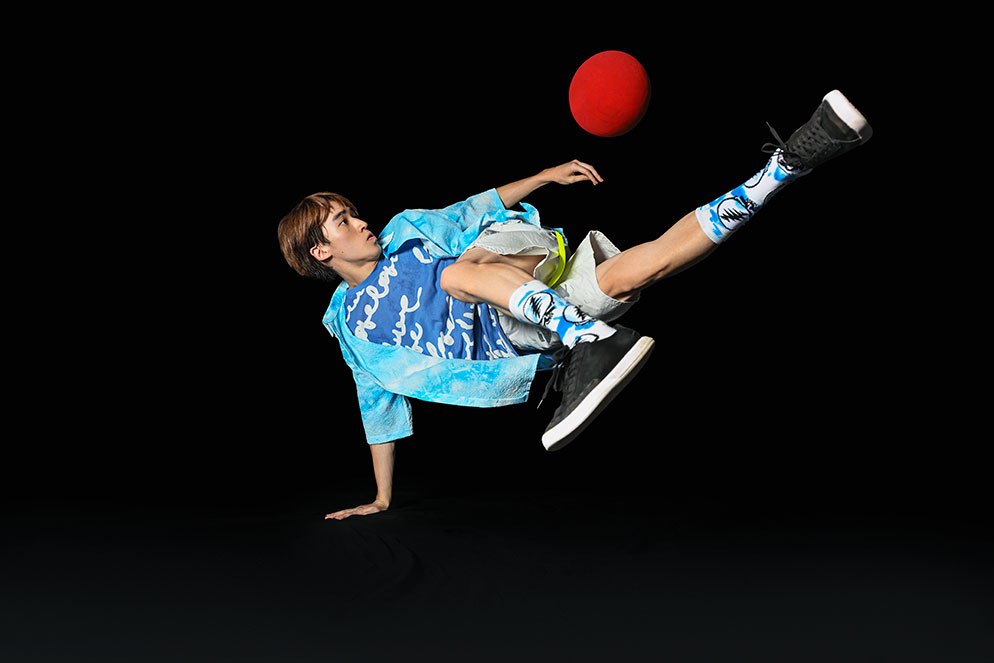

Freestyle football is a jumping, spinning, turning, twisting combination of football, breakdancing and performance art. Because the freestyler’s eyes are on the ball, the Z 9 had no trouble locking on and keeping up with the unpredictable action. Z 9, NIKKOR Z 14-24mm f/2.8 S, 1/200 second, f/2.8, ISO 160, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

We want to be clear about this: the Z 9 does not make the impossible possible.

What it does is enable photographers to create pictures that were once out of reach.

One of those photographers is Nikon Ambassador Matthew Jordan Smith. “I’ve always loved shooting fast glass wide open,” Matthew says, “but you can’t do that when you’re moving really fast.”

But that was exactly what he was doing for the photos you see here.

“You can’t shoot an f/1.4 lens and have somebody moving around and get focus,” he adds.

Which also happened for these photos.

“The Z 9 made that all possible,” he explains, “and that blew me away.”

So let’s say the Z 9 expands the realm of the possible.

Matthew was way ahead of that.

“It’s a heavy kimono, so to make it move, you have to do a lot of fast moving,” Matthew says. “This moment is at the end of a cut motion, and you see how her sleeve is in the midst of motion, an instant in the total fight scene she’s given me. Sharpness on the eye catches sharpness on everything.” Z 9, NIKKOR Z MC 105mm f/2.8 VR S, 1/200 second, f/2.8, ISO 320, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

The Eyes Have It

“I wanted to push the boundaries, not only to photograph things moving extremely fast, but things moving so fast you just can’t see them happening. That’s why in sports you have instant replay.”

Things happening so fast that he couldn’t see them, and photograph them anyway— things like the moves of a samurai. “True samurai swordsmen are extremely fast, and graceful and beautiful, and here in Tokyo there are a lot of actors who play those roles in movies. I’ve met a few of them, and when they’re fighting it’s like a dance—but a dance that’s over so fast you didn’t see everything that happened. I wanted to test that, to see if the Z 9 could keep up with it.”

It could, and it did. But that still wasn’t enough.

“There’s a new sport I found out about recently—freestyle football. It’s like a combination of breakdancing and football, and it moves very, very fast.” He thought if he could shoot it wide open with, say, an f/2.8 lens, that would be a gamechanger for what he could do in the future.

“If somebody is coming fast, straight at you, that might be a little easier, but a freestyle footballer is spinning, jumping, turning so fast you could never focus on his body, especially at wide-open apertures.”

What made it possible was Eye AF. “Even if it saw just the corner of his eye as he turned, the eye was still in focus. That was impressive.”

And even more so with the samurai fighter. “That was insane—she’s a performer and a stuntwoman, and she was moving faster than you can believe possible. She had on a giant kimono and the fabric would get in the way of her eye, but the instant the fabric was out of the way, the camera would pick up her eye.

“At one point I photographed her with two gigantic fans, and their material was covering her eye most of the time, but the camera would catch it every time it would peek through. Think of that. It opens up possibilities for things I could not do before.”

“Martial arts looks almost like a dance at times. I was awed by the performance—the athleticism, the precision, the beauty—and by the ability of the camera to catch movement in mid-movement. And I’m moving at the same time, changing angles. Still photography isn’t still, not anymore.” Z 9, NIKKOR Z 14-24mm f/2.8 S, 1/200 second, f/2.8, ISO 320, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

...the Z 9 expands the realm of the possible.

“You get a clue to how fast she’s moving by the garments and the fans. To make all that material move, to keep it going, to keep it visually effective takes speed and strength. If this weren’t the Z 9, locked on at 20 frames a second, I’d have been saying, ‘Can you do that again, only slower?’” Z 9, NIKKOR Z 14-24mm f/2.8 S, 1/200 second, f/2.8, ISO 320, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

Wide Open and Be There

“Shooting at f/8 looks a certain way,” Matthew says in a tone that suggests it is not the way he wants his photos to look. “At a wide-open aperture, the area of focus is so narrow, so slim, that everything else falls away to a beautiful bokeh. Shooting wide open makes an image look almost painterly. Now I can get that look, and motion and energy, and let everything else besides the eyes be super soft. That’s absolutely stunning.”

And once again, there’s even more to it. He knows the shots will be sharp where he wants them sharp, so he can be completely in the moment with his subjects, with no need to check frames for sharpness.

“When you have to focus on the tech, making sure everything’s on, you’re pulled away from being creative, from capturing the moment in a way where you feel free, and it’s fun.”

There’s also no need to be saying to a model, “Can you do that again?”

Unless, of course, you’re looking for a different angle, a different composition. But not likely a different aperture.

The black velvet drape in Matthew’s studio goes to the floor and across it, likely prompting a spontaneous breakdancing move that had no chance of speeding past the Z 9’s Eye AF lock-on. Z9, NIKKOR Z 14-24mm f/2.8 S, 1/200 second, f/2.8, ISO 320, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

File Under: Efficiency

For Matthew, large files and image quality are vital, and not only for the immediate assignment. His client might want images for the internet, but Matthew’s going to produce large, high-quality files because…well, you never can tell.

“I’m thinking in terms of the future and my archives. Maybe 10 or 20 years from now I’ll want to do a retrospective of my work and I’ll need huge prints; can’t make them from small files. I’ve always wanted the largest files so I have the ability to do more with them in the future.”

The Z 9’s 45.7-megapixel power will give him what he wants, and with its 20-, 30- and 120-frames per second frame advance, he can get a lot of what he wants. It seemed that high-capacity hard drives for storage and backup would be on the agenda.

Well, they are, but the Z 9 marks the debut of a new Nikon RAW file format—High Efficiency RAW *— that’s going to make a difference. Matthew’s aware of the benefit. “If I can have a smaller-size file and great quality—that’s a breakthrough.”

Here’s how the breakthrough breaks down.

The Z 9 offers a few file choices:

Lossless Compressed preserves all image information in a slightly smaller file than an uncompressed one.

The High Efficiency file strikes a balance between as-small-as-possible and highest-image-quality possible.

High Efficiency RAW * is half the size of uncompressed RAW and High Efficiency RAW is a third the size.

Simply, the High Efficiency RAW * file offers quality that’s practically indistinguishable from other RAW files. It lets you run longer sequences with practically no discernable loss of image quality. You can keep shooting at the frame rate you want and get the images you want before the camera will slow down to let the buffer catch up. The takeaway: High Efficiency RAW * means no loss of image quality and a big gain in all the good stuff.

When you choose the RAW format as your Z 9’s default, you get High Efficiency Raw * automatically; it is the RAW file default (JPEG is the default for the camera out of the box).

Matthew will make High Efficiency RAW * part of his workflow. “If I can have high quality in a smaller file, that’s something I want—great file, small size, love that.”

Just pushing the possible.

Z 9 In Action - There are two words that photographers want their inner voice to say: “Got it!” Spend a few minutes with Matthew Jordan Smith and see why he can now rely on those words as never before.